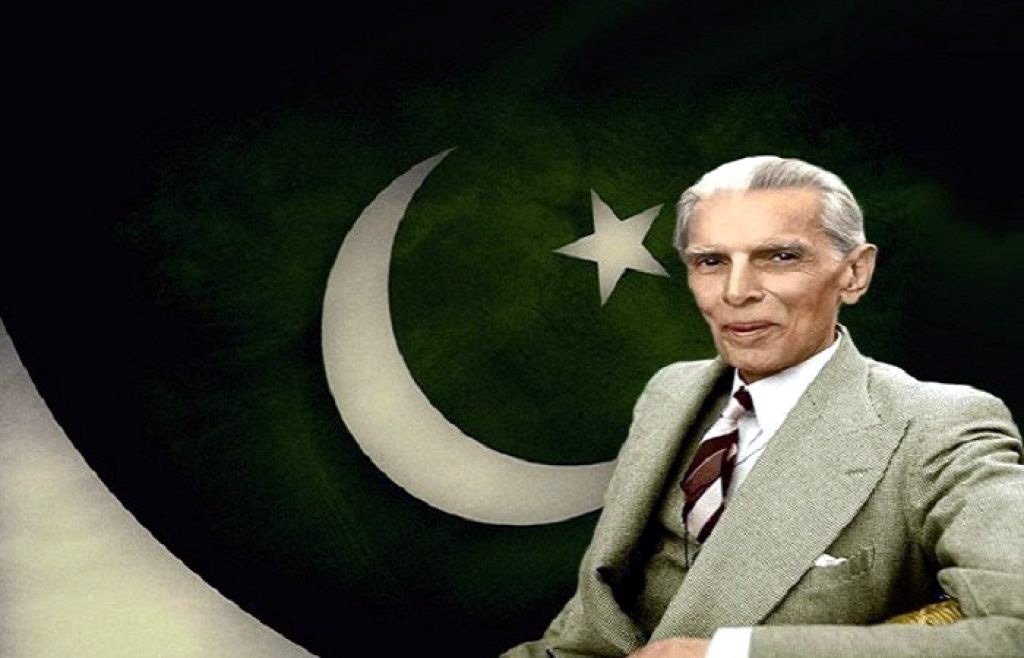

Quaid e Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, a name synonymous with the creation and establishment of Pakistan, stands as an unparalleled figure in the annals of history. Renowned as the founder of Pakistan, his indomitable will and unwavering commitment sculpted the contours of a new nation on the map of the world. The significance of his contributions cannot be overstated, as they laid the foundation for the emergence of a sovereign state aimed at providing a separate homeland for Muslims in the Indian subcontinent. His vision, diplomacy, and political acumen were instrumental in navigating the complex process of partition and ensuring the realization of Pakistan.

The article charts the journey of Quaid e Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah from his early life and education, through his legal career and political entry, to his pivotal role in the Indian independence movement. It explores his transformation into a fervent advocate of Muslim nationalism and his determined campaign for the creation of Pakistan. Each section delves into the critical milestones and the challenges he faced, culminating in the historic achievement of independence in 1947. His legacy and impact are enduring, shaping the ideological and cultural framework of the nation he founded. The conclusion reflects on the profound influence Jinnah had on Pakistan and the enduring relevance of his vision.

Early Life and Education

Family Background

Muhammad Ali Jinnah was born into a Gujarati-speaking Lohana family of the Thakkar caste, originally from Kathiawar, Bombay Province. The family moved to Karachi in 1875, where they were engaged in commerce [7]. His father, Jinnahbhai Poonja, was a prosperous merchant and a member of the Khoja sect, Hindus who had converted to Islam centuries earlier and followed the Aga Khan [5][6]. Jinnah was the eldest of seven children, raised in a household that transitioned from Hindu customs to Islamic teachings during his early years [10][16].

Schooling and College

Jinnah’s formal education began at home, followed by schooling at the Sind Madrasat al-Islam in Karachi. He later attended the Christian Missionary Society High School, where he excelled academically, passing the matriculation examination of the University of Bombay at the age of 16 [5]. This early education laid the groundwork for his proficient use of the English language, which later became a significant tool in his legal and political career [18][19][20].

Education in England

In pursuit of higher education, Jinnah traveled to England in 1892. Initially, he joined a business apprenticeship, but soon decided to study law, enrolling at Lincoln’s Inn. Despite familial opposition and personal bereavements, Jinnah was determined to become a barrister. He was called to the bar in 1895, at the age of 19 [22][24][25]. His time in England was not just about legal studies; it also involved a deep engagement with the British political system, which influenced his later political strategies [24].

Legal Career

Early Struggles

Muhammad Ali Jinnah began his legal practice in Bombay at the age of 20, becoming the only Muslim barrister in the city. Despite his proficiency in English, he faced initial challenges with very few legal briefs coming his way from 1897 to 1900 [14][18]. His legal career took a positive turn when he was invited to work from the chambers of the acting Advocate General of Bombay, John Molesworth MacPherson, which marked the beginning of his rise in the legal profession [14]. In 1900, he was temporarily appointed as a Presidency Magistrate in Bombay, a position he held for six months before declining a permanent offer, ambitiously stating his goal to earn 1,500 rupees a day [14][17].

Major Legal Cases

Jinnah’s legal acumen became particularly evident with his involvement in several high-profile cases. The “Caucus Case” of 1908 was a significant milestone where he successfully challenged the election of a municipal candidate, enhancing his reputation as a skilled lawyer [14][16]. This case involved allegations of electoral manipulation by a group known as the “caucus” to exclude Sir Pherozeshah Mehta from the Bombay Municipal Corporation [16].

Another notable case was when Jinnah defended Bal Gangadhar Tilak, a prominent leader of the Indian National Congress, who was charged with sedition in 1916. Although Jinnah did not succeed in securing Tilak’s release on bail initially, he managed to obtain an acquittal for him later, which was a testament to his growing legal prowess [14].

Jinnah also represented various clients in civil and criminal cases, demonstrating his versatility and command over legal matters. His defense in the Bowla Murder case and the well-known defamation case involving B.G. Horniman are examples of his capacity to handle sensational and complex cases successfully [16]. Moreover, his legal strategies in the Caucus Case of 1905 further solidified his status as an outstanding lawyer in India [16].

Throughout his legal career, Jinnah earned a reputation for his sharp legal mind and his ability to present clear and persuasive arguments. These early experiences in the courtroom not only established him as a prominent lawyer but also paved the way for his later political career, where he continued to use his legal expertise to advocate for the rights and independence of the Indian people [14][16][17].

Political Entry

Joining the Congress

Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s formal political journey began when he attended the Indian National Congress’s twentieth annual meeting in Bombay in December 1904 [19]. His initial political stance was as a member of the moderate group within the Congress, where he advocated for Hindu-Muslim unity in the pursuit of self-government. He was influenced by leaders such as Mehta, Naoroji, and Gokhale, who were prominent figures in the Congress [19][20]. Jinnah’s political ideology at this time was characterized by a strong admiration for British political institutions and a desire to elevate India’s status internationally, while fostering a sense of Indian nationhood [20].

In 1906, Jinnah participated in the Congress session held in Calcutta, where the party’s views began to diverge between those seeking dominion status and those demanding complete independence for India [20]. His commitment to the Congress was further deepened when he served as Secretary to Dadabhai Noaroji, the then President of the Indian National Congress, during the Calcutta Congress session in December 1906. This role was a significant honor for Jinnah, marking his growing influence in political circles [24].

First Political Activities

Jinnah’s early political activities were not limited to his involvement with the Indian National Congress. He was also vocal about his concerns regarding the representation of Indian Muslims. In 1906, following the meeting of a delegation of Muslim leaders with the Viceroy of India, known as the Simla Delegation, Jinnah criticized the delegation for claiming to represent all Indian Muslims without being elected or appointed by the community [19]. He expressed these views through a letter to the editor of the Gujarati newspaper, questioning the legitimacy of the delegation’s claims [19].

Despite his initial reservations about exclusive Muslim representation, Jinnah’s political career took a significant turn when he joined the All-India Muslim League in 1913. Prior to this, he had been critical of the League’s formation in Dacca in 1906, where he disagreed with the approach taken by many Muslim leaders [19]. However, by 1913, his perspective had shifted, recognizing the need for a platform to specifically address Muslim interests within the broader nationalistic movement [21].

His dual membership in both the Congress and the Muslim League was unique, and he emphasized that his allegiance to the League did not undermine his commitment to the Indian National Congress and the overarching goal of an independent India. This dual role allowed him to serve as a bridge between the two communities, striving for unity and cooperation [19]. In 1916, as president of the Muslim League, Jinnah played a crucial role in the signing of the Lucknow Pact, a significant agreement between the Congress and the League, which set quotas for Muslim and Hindu representation in various provinces. This pact was a testament to his enduring commitment to Hindu-Muslim unity and his skillful negotiation abilities [19].

Role in Indian Independence

Advocating Hindu-Muslim Unity

Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s early political career was marked by a strong belief in Hindu-Muslim unity, which he supported passionately for nearly three decades since his entry into politics in 1906 [27]. His advocacy for unity was evident when he worked alongside Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who once praised Jinnah for his freedom from sectarian prejudice, suggesting that he had the potential to become the best ambassador for Hindu-Muslim unity [27]. This period was crucial as it set the stage for Jinnah’s significant contributions to Indian politics, particularly through the Congress-League Pact of 1916, popularly known as the Lucknow Pact [27].

The Lucknow Pact

The Lucknow Pact of 1916 was a landmark agreement between the Indian National Congress and the All-India Muslim League, which Jinnah had joined by then. This pact was significant as it marked the first time that Hindus and Muslims made a joint demand for political reform to the British [29][30]. It was seen as a beacon of hope for Hindu-Muslim unity and a high-water mark in their cooperative efforts [29][30].

The agreement included several key provisions that catered to Muslim interests, such as separate electorates for Muslims in provincial council elections and weightage in their favor in all provinces except Punjab and Bengal [28][29]. These concessions were a departure from previous positions held by the Congress, particularly their initial rejection of separate electorates in the Morley-Minto reforms [29]. The pact also established quotas for Muslim and Hindu representation in the various provinces, which, although never fully implemented, ushered in a period of cooperation between the Congress and the League [26].

The signing of the Lucknow Pact also helped to mend relations within the Indian National Congress between the ‘extremist’ faction led by figures like Lala Lajpat Rai and the ‘moderate’ faction represented by leaders such as Gandhi [29]. Jinnah’s role was pivotal in these developments, as he managed to bridge differences between various groups and advocate effectively for the interests of both Hindu and Muslim communities [30].

Overall, the Lucknow Pact not only facilitated Hindu-Muslim cooperation during the Khilafat movement and Gandhi’s non-cooperation movement but also laid the groundwork for subsequent political reforms in India, including the Government of India Act of 1919 [28][30]. Jinnah’s efforts during this time earned him the title of “the Ambassador of Hindu-Muslim Unity,” a testament to his significant impact on Indian politics and his vision for a unified approach to achieving self-governance [30].

Shift towards Muslim Nationalism

Emergence of the Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League was established in 1906 to represent the interests of the Muslim population and to counter the perceived dominance of Hindus under British rule [32]. The formation of the League was a response to the overwhelming representation of Hindus in the Indian National Congress, which was formed to advocate for the indigenous people of British India [31]. The League aimed to safeguard Muslim interests by advocating for separate electorates and reserved seats, which they achieved in part through the Indian Councils Act [32].

Jinnah’s Leadership

Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s leadership of the Muslim League marked a pivotal shift towards Muslim nationalism. Initially a member of the Indian National Congress, Jinnah became disillusioned with the party’s approach and joined the Muslim League in 1913, after being assured of its commitment to the political emancipation of India [35]. His leadership was characterized by a pragmatic approach to politics, favoring legal methods and negotiations over the civil disobedience tactics employed by Gandhi [31].

The concept of Pakistan, initially proposed by philosopher Sir Muhammad Iqbal, gained Jinnah’s support as he became convinced that a separate Muslim state was the only solution to protect Muslim interests [35]. This realization was crystallized during the Lahore Resolution in 1940, where the demand for a separate Muslim nation was formally adopted [34]. Jinnah’s adept leadership and steadfast advocacy for Muslim nationalism culminated in the creation of Pakistan in 1947, following the failure of power-sharing negotiations with the Congress [34]. His role as the first governor-general of Pakistan was crucial in establishing the new nation’s government and policies, particularly in managing the massive influx of Muslim migrants from India [34].

Demand for Pakistan

Two-Nation Theory

The concept of the Two-Nation Theory, which posited that Muslims and Hindus were two distinct nations with divergent social, cultural, and religious ideologies, was central to the demand for Pakistan. This theory argued that Muslims would not thrive in a Hindu-majority India and therefore required a separate nation where they could have equal rights and self-governance [37][38]. Prominent leaders like Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Allama Iqbal articulated this perspective, emphasizing that Muslims and Hindus belonged to different civilizations, which made their coexistence under one government problematic [37][38][39].

The All-India Muslim League, under Jinnah’s leadership, adopted this theory as the foundational principle for the Pakistan Movement, advocating for a separate Muslim state [37]. This demand was initially for autonomous and sovereign states within a united India but eventually evolved into the call for a completely independent Pakistan [38].

Lahore Resolution

The Lahore Resolution, passed on 22-24 March 1940, marked a definitive moment in the history of the Pakistan Movement. Authored by Muhammad Zafarullah Khan and presented by A.K. Fazlul Huq, the resolution called for the formation of independent states in regions where Muslims were the majority [40]. This resolution did not explicitly mention “Pakistan,” but it laid the groundwork for the future nation’s conceptualization [40].

Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s transformation into a staunch advocate for a separate Muslim homeland was significantly highlighted during his address at the Lahore conference. His speech underscored the resolution’s importance and set the stage for the formal demand for Pakistan [40][41]. The resolution was met with mixed reactions, gaining enthusiastic support from Muslim communities while facing strong opposition from the Hindu leadership and press, who quickly termed it the demand for Pakistan [40][41].

The Lahore Resolution also strategically addressed the geopolitical configurations, proposing that contiguous units in the north-western and eastern zones of British India, where Muslims were in the majority, should be grouped to form independent states [40]. This plan was further affirmed in the subsequent years, leading to the eventual realization of Pakistan in 1947 [42].

The commemoration of this pivotal event is observed as Pakistan Day on 23 March, celebrating both the Lahore Resolution and the establishment of the Republic in 1956, marking the country’s identity as the first Islamic Republic in the world [40].

Creation of Pakistan

Political Negotiations

The journey towards the creation of Pakistan was marked by intense political negotiations involving key figures such as Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Jawaharlal Nehru, and the British administration. By 1940, Jinnah had firmly come to believe that Muslims in the Indian subcontinent should have their own state to avoid potential marginalization in a dominantly Hindu nation. This belief was strongly articulated during the Lahore Resolution, which demanded a separate nation for Indian Muslims [48]. The resolution catalyzed the Muslim League’s efforts, which gained momentum during the Second World War as the Congress leaders were incarcerated, allowing the League to win most of the Muslim-reserved seats in the subsequent provincial elections [48].

These unfolding events set the stage for the Cabinet Mission in 1946, which was tasked with negotiating the terms for a peaceful transfer of power from British rule. The mission proposed a federal structure with significant autonomy for provinces but failed to bridge the widening gap between the Congress and the Muslim League, primarily over the issue of Pakistan [44]. Jinnah, utilizing his legal acumen and political foresight, managed to interpret the mission’s proposals as a foundation for Pakistan, which led to the Muslim League’s acceptance of the plan [44]. However, the inability to reach a comprehensive power-sharing agreement eventually led all parties to consent to the partition of India and the creation of an independent Pakistan [48].

Partition Plan

The partition of British India into India and Pakistan in August 1947 marked the culmination of a series of negotiations and political maneuvers. The communal riots of 1946 had escalated to alarming levels, indicating a dire need for a resolution. Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of British India, was pivotal in orchestrating the Partition Plan. His negotiations with Indian political leaders led to the acceptance of a plan on 3 June 1947, which proposed the division of the subcontinent and the establishment of two independent states by 15 August 1947 [44].

This plan, accepted by the Congress, the Muslim League, and the Akali Dal, aimed to address the administrative and political challenges posed by the diverse and often conflicting interests of the subcontinent’s population. The plan’s implementation led to the creation of West and East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh), marking a significant geopolitical shift in South Asia [46]. Jinnah, who had long advocated for a separate Muslim nation, became the first governor-general of Pakistan. Despite achieving his goal, Jinnah expressed concerns over the partition’s outcome, referring to Pakistan as a “moth-eaten” state, reflecting his dissatisfaction with the territories allocated to Pakistan [46].

In his role as governor-general, Jinnah was instrumental in establishing the new nation’s government and policies, particularly focusing on managing the massive migration of Muslims from India to Pakistan, and setting up refugee camps to accommodate the influx [48]. This period was critical in laying the foundational governance structures of Pakistan, amidst the backdrop of significant social and political upheaval.

Legacy and Impact

Governor-General of Pakistan

Muhammad Ali Jinnah served as the first Governor-General of Pakistan, a role in which he was not just a ceremonial head but the driving force behind the establishment of the nation’s government and policies [52][53]. During his tenure, Jinnah tackled the immense challenges facing the nascent state with authoritative leadership. He was instrumental in addressing the issues of millions of Muslim migrants who had moved from India to Pakistan following independence, personally overseeing the setup of refugee camps [53][49]. His efforts during this critical period were pivotal in stabilizing Pakistan amidst the chaos that surrounded its birth [54].

Despite the severe administrative, economic, and military challenges, including an empty treasury and the absence of a central government, Jinnah’s leadership was crucial. He utilized his immense prestige and the loyalty he commanded to energize the Pakistani people, raising their morale and directing their patriotic fervor towards nation-building [54]. His policies laid the foundations of the Pakistani state and addressed immediate problems like maintaining law and order and integrating refugees into the society [54].

Historical and Cultural Influence

Jinnah’s impact extends beyond his political and administrative contributions; he left a profound legacy that continues to shape Pakistan’s ideological and cultural framework. Revered as Quaid-e-Azam (Great Leader) and Baba-e-Qaum (Father of the Nation), his vision for Pakistan as a separate homeland for Muslims to safeguard their rights and way of life resonates deeply within the country’s national identity [53][50]. His birthday is celebrated as a national holiday, reflecting his enduring presence in the collective memory of the Pakistani people [53].

Public buildings and several universities in Pakistan bear Jinnah’s name, signifying his lasting influence on the nation’s educational and infrastructural development [53][50]. His role in the creation of Pakistan and his leadership during its formative years have been lauded by historians and scholars, with his biographer Stanley Wolpert recognizing him as Pakistan’s greatest leader [53][50].

Jinnah’s death in September 1948, just over a year after Pakistan’s independence, marked the end of an era. However, the foundations he laid for the country have ensured his legacy continues to be celebrated and respected [52][53]. His leadership not only guided Pakistan through its tumultuous early years but also set the course for its future, making him a central figure in South Asian history [54].

Conclusion

Throughout this article, we revisited the monumental journey and undeniable legacy of Quaid e Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the monumental figure whose vision and determination were fundamental in carving out the nation of Pakistan from the clutches of colonial rule. In reflection, we traced his evolution from a fervent advocate of Hindu-Muslim unity to the unwavering spearhead of Muslim nationalism, elucidating the critical milestones that culminated in the realization of Pakistan. His unyielding approach, political acumen, and legal expertise not only navigated the tumultuous waters of independence but also laid the foundational ethos of a new nation, emphasizing his status as the ‘Father of the Nation.’

In his final years, Jinnah’s leadership as the Governor-General of Pakistan was marked by challenges and triumphs, shaping the embryonic state amidst myriad adversities. His passing in September 1948, just a year after the creation of Pakistan, left an indelible void; yet, his enduring legacy continues to inspire and guide the nation. Jinnah’s vision, exemplified through his commitment to equality, justice, and unwavering dedication to his people, remains a beacon for the future, reinforcing his role as not just the architect of an independent Pakistan but also as a symbol of hope and unity for generations to come.

FAQs

Who was the founder of Pakistan known as Quaid-e-Azam?

Mohammad Ali Jinnah (December 25, 1876 – September 11, 1948) was a prominent lawyer, politician, and statesman in the 20th century who founded Pakistan. He is widely revered and officially recognized in Pakistan as Quaid-e-Azam (“Great Leader”) and Baba-e-Qaum (“Father of the Nation”).

What contributions did Jinnah make to establish Pakistan?

As the first governor-general of Pakistan, Jinnah was instrumental in setting up the country’s government and policies. He played a crucial role in assisting the Muslim migrants who moved from India to Pakistan following the independence of both states, including personally overseeing the creation of refugee camps.

What is Muhammad Ali Jinnah renowned for?

Muhammad Ali Jinnah is best known as the founder and first governor-general (1947–48) of Pakistan, and he is honored as the father of the nation. His efforts to achieve political unity between Hindus and Muslims earned him the title of “the best ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity.”

What was Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s educational background?

Born into a well-known mercantile family in Karachi on December 25, 1876, Jinnah was educated at the Sindh Madrassat-ul-Islam and the Christian Mission School in his hometown. He later joined Lincoln’s Inn in 1893, becoming the youngest Indian to be called to the Bar three years later.

References

[1] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[2] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[3] – https://pid.gov.pk/site/profile/1

[4] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jinnah_family

[5] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[7] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[8] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[9] – https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah

[10] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[11] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[12] – https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/jinnah_mohammad_ali.shtml

[13] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[14] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[15] – https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah

[16] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caucus_Case

[17] – http://www.nihcr.edu.pk/downloads/qa.pdf

[18] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[19] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[20] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[21] – https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/jinnah_mohammad_ali.shtml

[22] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[23] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[24] – https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah

[25] – https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-40961603

[26] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[27] – https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah

[28] – https://www.britannica.com/event/Lucknow-Pact

[29] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lucknow_Pact

[30] – https://unacademy.com/content/mppsc/study-material/history/the-lucknow-pact-1916/

[31] – https://www.britannica.com/place/Pakistan/The-Muslim-League-and-Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[32] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All-India_Muslim_League

[33] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pakistan_Muslim_League_(Jinnah)

[34] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[35] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[36] – https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/evolutionofparliament/legislativescrutiny/parliament-and-empire/collections1/collections2/jinnah-and-the-muslim-league/

[37] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two-nation_theory

[38] – https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/37726

[39] – https://www.britannica.com/place/Pakistan/The-Muslim-League-and-Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[40] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lahore_Resolution

[41] – https://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/history/PDF-FILES/8-%20PC%20Farooq%20A%20Dar_52-1-15.pdf

[42] – https://thefridaytimes.com/19-Mar-2024/the-lahore-resolution-and-the-reaction-of-the-nationalist-muslims

[43] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[44] – https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah

[45] – https://bestdiplomats.org/quaid-e-azam-role-in-creation-of-pakistan/

[46] – https://www.history.ox.ac.uk/why-was-british-india-partitioned-in-1947-considering-the-role-of-muhammad-ali-0

[47] – https://www.neliti.com/publications/263018/role-of-jinnah-in-partition-of-india-pakistan

[48] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[49] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[50] – https://pid.gov.pk/site/profile/1

[51] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[52] – https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohammed-Ali-Jinnah

[53] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[54] – https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah

[55] – https://www.pakistanembassytokyo.com/content/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah

[56] – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammad_Ali_Jinnah

[57] – https://www.dawn.com/news/1377353